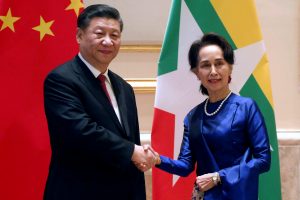

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Myanmar’s State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi shake hands at the Presidential Palace in Naypyitaw, Myanmar Jan.17. Photo Credit: Reuters

A significant highlight of the recent visit by the Chinese President Xi Jinping to Myanmar was his meeting with the Burmese State Counselor, Aung San Suu Kyi. The two leaders with strikingly different personalities and more so a distinct beginning of their political course, have paradoxically acknowledged each other’s interests. Suu Kyi is a well-known international figure, a Nobel Laureate and a celebrated freedom fighter in her home country. After her ascension to a de facto leader in 2016, her government was heavily criticized for the violence unleashed on the Rohingya Muslims. The current Burmese government faces sanctions from Western nations over human rights violations while Suu Kyi’s growing unpopularity over her indiscretion on Rohingya Muslims has added to her declining international prestige. Under such circumstances, Xi Jinping’s visit to Myanmar could not have come at a better time, calling Myanmar a ‘trusted friend’, allying against Western pressure and intrusion. In fact, Dai Yonghong of Shenzhen University argues that the Western approach to human rights issues has always been double standard and that China came in rescue of Myanmar at this difficult time. Amidst international pressure imposed on Myanmar, Aung San Suu Kyi and China both reached a mutual agreement over their opposition to external interference in their internal affairs. This current status of Myanmar compliments China’s neighbourhood diplomacy, integrating Myanmar into the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and laying the foundation for building of a new type of international relations. The new kind of international setting that favours Beijing and create a favourable external environment for China’s growth and power to influence, has time and again challenged Western establishment and norms. Quite interestingly, China sees itself as norm changer rather norm breaker and with its economic power and political influence at its disposal, Beijing intends to deepen its ties at all levels.

The deepening of the bilateral relations between China and Myanmar have many dimensions to it, among which, one particular issue of importance is securing its border and maintaining stability in the neighbouring countries. Noting that Myanmar is a Buddhist dominated region, Beijing wants to make sure that the conflicts within regions like Tibet and Xinjiang do not escalate and have spillover effects. In this regard, Xi Jinping has specifically mentioned that China not only supports Myanmar in ‘safeguarding its legitimate rights and interests and national dignity in the international arena’, but that Myanmar should also return the favour by extending their support on issues involving China’s core interest and major concerns. Conforming to China’s territorial integrity is respecting China’s core interest thereby indicating that Tibet, Xinjiang and Taiwan are all indispensable parts of China. Such agreement was reached in the bilateral relations of China and Myanmar. As a matter of fact, the commitment to the One China Policy and Myanmar’s support to China’s treatment over Tibet and Xinjiang was uncalled for. In an immediate response to the Joint accord signed between China and Myanmar, the Central Tibetan Administration condemned these respective provisions of the Agreement that concede to the One China Policy, recognizing Tibet as part of China in the process. Noting that Beijing consistently seeks from every country, without exception, a reference to One China Policy in their bilateral relations which is seen as a fundamental Chinese core concern nevertheless reflect deep-rooted insecurity over its legitimacy in regions such as Tibet, Xinjiang and Taiwan. This exclusive importance of the One China Policy, for instance is an official exchange assurance from a foreign government over sensitive regions like Tibet, Xinjiang and Taiwan as part of China in return for huge economic incentives. Under the model of win-win cooperation based on mutual respect, Beijing attempts to increase mutual political trust with foreign heads of government, thereby, holding strategic positions in their foreign policy direction.

Xi Jinping, during his state visit to Myanmar, the first one by a Chinese president in 19 years after Jiang Zemin in 2001, called it the traditional “pauk-phaw” (fraternal) relations between China and Myanmar. Xi’s visit was not only the first official visit made in 2020, but it also marks the 70th anniversary of the establishment of China-Myanmar diplomatic relations. Calling the visit a ‘new milestone’, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Myanmar believe it to have ‘opened a new chapter in the ever-lasting friendship’ between the two countries.

However, many observers reveal Myanmar’s dramatic growing dependence on China since the major focus of the “pauk-phaw” relations between China and Myanmar is the economic dimension, a vital part of which is including Myanmar in Xi’s pet project, the BRI. This revisited relationship has made irked India’s apprehension over the challenges it will pose for itself, particularly in light of China’s growing presence in Nepal which was accentuated by Xi’s visit to Kathmandu last year. Since both Myanmar and Nepal borders India and with its recent altercations with China, India’s defensiveness is a natural reaction to China’s growing influence in these countries. The seemingly inevitable presence of China in South Asia is evident and spreading, as seen in countries such as Nepal and Myanmar. With China’s recent push for its BRI project, south Asian countries are increasingly bandwagoning with Beijing as it attempts to securitize its regime as well as reflect its influence outwards. The question that therefore remains to be answered is whether this alignment of South Asian countries reflect a new power dynamic that is largely influenced by Chinese interests and norms.

*Tenzin Lhadon is a visiting fellow of Tibet Policy Institute. She is a Ph.D scholar from Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi. Views expressed here do not necessarily reflects those of the Tibet Policy Institute.