For as long as space endures

And for as long as living beings remain,

Until then may I, too, abide

To dispel the misery of the world

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet regularly cites this verse as a source of “great inspiration of determination” (Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet, 299). Perhaps that is why decades down the line, despite the disastrous events that happened in Tibet, he continues to tirelessly fight for the betterment of the Tibetan people, as well for the global community to embrace the simple teaching of compassion.

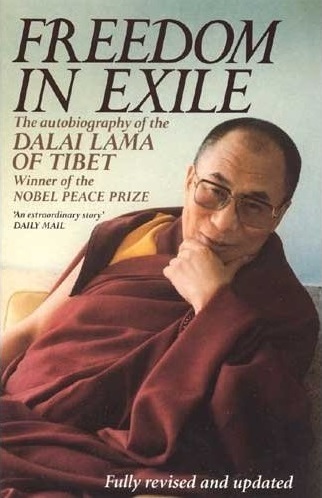

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama’s second autobiography, “Freedom in Exile” serves not only as the well accounted, and heartfelt narration of the events that shaped his life, but as a reminder of the tragic events in Tibetan history, and the effects of those events on the Tibetan and global community today. This story follows the journey of young boy, unaware of his future, to the global leader, and the recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize award, whose words of peace and compassion resonate among millions today. Above all, it is the quintessential story of hope, through the darkest nights.

The narration begins with the discovery of a little boy in the Takster, a village tucked away in the crevices of the remote Tibetan region of Amdo. Although the boy, no more than two years old, suffered from the occasional bouts of naughtiness, he was, seemingly, quite ordinary. That is, until he was discovered to be the reincarnation of the 13th Dalai Lama. In retrospect, the boy’s insistence on a journey to Lhasa, or his inexplicable amicability toward strangers could have been early signs to the boy’s future. The boy was born 6th July 1935, called Lhamo Thondup, and short while later, he would be discovered as the highest authority of Tibetan spirituality.

The story follows the relatively regular childhood of Lhamo Thondup, who at the age of five, forfeited that name in favor of the name his regent gave him. The world was introduced to Tibet’s new Dalai Lama, Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Yeshe Tenzin Gyatso. As a young child, the HH the Dalai Lama had no qualms in spending his days roaming the grounds of his summer palace, Norbulingka, or sulking at the thought of the dingy, dark rooms of his winter palace, the Potala. He spent his days as most children his age did, playing with the sweepers, getting in to various degrees of trouble, and trying very hard to avoid any responsibility. And although as young monk his attention span betrayed him during his prayers, he was, all in all, happy.

As the threat to Tibetan independence materialized from China’s growing interest in Tibet, the young monk found himself in the crosshairs of the political firestorm brewing, his spiritual duties, and his duties to the people. For any normal adolescent, this would be a moment of indecision in their lives. However, HH the Dalai Lama was, by no definition, normal.

“[…] I found myself the undisputed leader of six million people facing the threat of full scaled war. And I was only fifteen years old” (Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet, 61).

Through the struggles for diplomacy, endless negotiations, countless deaths, and finally, the desperate escape into India, there is one common denominator: Faith. And faith need not be religious. Some may have faith in a God, or deity, or particular religion, while others may have faith in technology, science, or humanity. There is faith for all. Perhaps, one of the numerous reasons for His Holiness’s will and personal strength, is his faith in all of the above. That and his strict vows to do the best for largest number of sentient beings.

“Freedom in Exile” recounts numerous tales of the vicious torture that Tibetans have faced at the hands of the Chinese authorities. This includes physical tortures that can hardly be put into words, as well as the attempt of meticulous and total annihilation of the people of Tibet, and its once rich and vibrant culture. Close to one and a quarter million Tibetan people were killed, in what is undoubtedly, a gross and blatant violation of human rights, as well as the very definition of genocide. This not only includes the people who were thrown in prisons of ghastly conditions, left to rot, or those who were executed and tortured to the point of death, but also the victims of starvation from the inefficacy of the Chinese regime to distribute food, as well as the thousands of people driven to suicide. The autobiography follows the journey of hundreds of thousands of Tibetans as they attempt to settle into a life in exile, including His Holiness.

In exile, the Tibetans struggled to acclimatize to their new surroundings, to rebuild their lives. And eventually, with the much appreciated support of the governments and leaders of various countries, such as India and Switzerland, and the generosity of many organizations and individuals, the Tibetan community in exile has managed to thrive. Today, there is a Central Tibetan Administration, a government in exile of sorts, to support the Tibetans living in various countries, as well as to further the Tibetan agenda to the right authorities. However, the situation in Tibet, continues to deteriorate.

The Dalai Lama has since devolved his political authority, and instead spends his time, although in exile, touring the world raising awareness for the Tibetan cause in the efforts to mold a better future for the Tibetans in and out of Tibet.

What makes this autobiography so special, is its simple, yet effective way of narrating a story, arming the reader with an adequate arsenal of facts, while simultaneously injecting the words with heartfelt emotion. Many a novel tries, and sometimes fails, to evoke emotions in the reader. “Freedom in Exile” does not seem to follow that conventional route. Instead of emotion, the author seems keen on provoking thought in the reader. HH the Dalai Lama, does not outwardly beg for the reader’s sympathy, but instead, lays out the story and leaves readers to answer the question and make their own choice. And although this tale is one of immense tragedy and loss, the author manages to find the frail silver lining, to this dark and gloomy cloud. The author’s optimism proves to be infectious, and his recollection of his actions and the actions of the people serve as a valuable tool for self-reflection. The reader is encouraged, by example of the author, to look within themselves, and be better.

Above all, the shining jewel in this autobiography is the utter sincerity of the words written. Through his writing, the author expresses an earnest gratitude to all those who have made contributions, however small they may be, to the Tibetan cause. The author’s recollection of this story proves the genuine care he feels for his people, as well as the magnitude of his vows of nonviolence and compassion. The author’s insistence on hope and compassion reveal a kind nature, incapable of harming others, and fueled on hope. And perhaps it is this hope, this faith that drives the author, and his people to continue to fight for the rights of Tibetans, even after long decades of struggle. Although the autobiography may not have been written for the sake of pleasing the reader, the compelling nature in which the narrative is laid out, coupled with the sincerity that rings out with every word, proves to be work of pure heart.

There is chapter in the autobiography, dealing with the supernatural aspects of Tibetan Buddhism, titled “Of ‘Magic and Mystery'”. Perhaps “Of ‘Magic and Mystery'” should have been the title of this autobiography. Because although the tragedies in Tibet are neither mysterious nor magical, the mystery behind the enigmatic figure and his narrative, suddenly becomes all too clear, and the courage of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan people, are undoubtedly, works of magic.

________________________

*Tenzin Yigha is an intern at the Tibet Policy Institute. Views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the Tibet Policy Institute.