Executive Summary

China’s language policy in Tibet reveals a fundamental contradiction between constitutional guarantees and actual implementation. While China’s constitution recognizes 56 ethnic minorities and ostensibly protects their linguistic rights, in practice, the Tibetan language faces systematic marginalization. This disconnect stems from China’s history of occupation in regions like Tibet, East Turkistan, and Mongolia. Under Xi Jinping, language policy has become increasingly aggressive, reflecting a shift toward a “one state, one language” model that prioritizes national unity over minority rights.

The Tibetan language, dating back to the 7th century, belongs to the Tibeto-Burman branch of the Sino-Tibetan macrofamily and differs completely from Chinese in grammar, vocabulary, and script. For over a millennium, it served as Tibet’s primary medium for teaching and transmitting knowledge. Following China’s invasion, Tibet’s traditional educational system was dismantled and replaced with a Soviet-influenced model that framed Tibetan culture as “backward” compared to “civilized” Chinese culture.

Legal frameworks have steadily eroded Tibetan’s status since the 1990s:

- The 1995 Law on Education began relegating minority languages from primary instructional languages to extracurricular subjects

- The 2000 Law on National Standard and Spoken Language further privileged Mandarin Chinese

- School curricula increasingly emphasize Han Chinese cultural norms and party ideology

Despite constitutional provisions stating that minority nationalities have the right to “conduct affairs in their own languages and independently develop education,” implementation contradicts these guarantees. Scholar Gerald Roche notes that institutional support for Tibetan pales in comparison to that for Putonghua (Mandarin Chinese), inevitably marginalizing the former. The PRC constitution prioritizes “national unity” over minority rights, effectively allowing authorities to suppress the Tibetan language by framing its use as “separatism.”

Under Xi Jinping, language suppression has intensified dramatically. His visits to Tibetan regions consistently emphasize:

- National security and stability in border regions

- “Sinicization” of Tibetan Buddhism

- Stronger recognition of Chinese national identity

- Promotion of Mandarin Chinese and nationally unified textbooks

Recent evidence demonstrates this intensification through multiple channels:

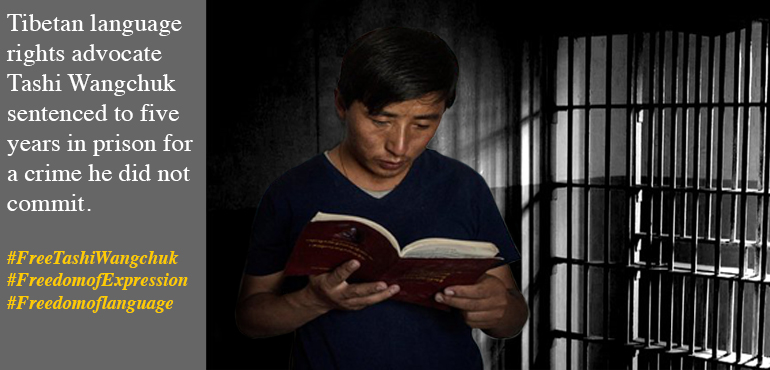

File Photo: China Sentences Tibetan Language Advocate Tashi Wangchuk to 5 Years/22-May 2018. Source: tibet.net

Persecution of Language Advocates: Gonpo Namgyal, a village leader advocating for Tibetan language preservation, died shortly after release from detention showing signs of torture. Tashi Wangchuk received a five-year prison sentence for advocating for language rights. Others like Tsering Dorje have been detained merely for discussing Tibetan language by phone.

New Restrictions: In 2025, Tibetan students were prohibited from receiving private Tibetan language lessons during winter break and instead directed to focus exclusively on improving their Mandarin.

Digital Censorship: Authorities have blocked numerous Tibetan-language websites, including the educational resource Luktsang Palyon. The Chinese version of TikTok (Douyin) has removed Tibetan language capabilities entirely.

School Closures: Since 2021, authorities have forcibly closed numerous Tibetan-language schools, including the award-winning Jigme Gyaltsen Nationalities Vocational High School and Taktsang Lhamo Kirti Monastery school (500 students). The Drakgo Monastery’s school was not only closed but demolished. Teachers and students who protested these actions, like Rinchen Kyi and Loten, face “separatism” charges. In Ngaba Prefecture alone, 69 primary schools have been completely closed.

The progression of policy shows a systematic shift from limited bilingual education to near-complete Chinese-medium instruction. Current policies visually prioritize Chinese in public spaces and mandate Chinese instruction from kindergarten onward. Policy language deliberately employs ambiguity to implement more restrictive measures than publicly stated. For example, the 2017 announcement that “bilingual education” reached “100 percent coverage” masked the reality that this meant primarily Chinese-medium instruction.

This systematic marginalization of Tibetan language represents an existential threat to Tibetan cultural identity and linguistic rights, with increasingly aggressive implementation under Xi Jinping’s leadership.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

Full Paper

China’s Language Policy in Tibet

The question of language policy in China, particularly minority language policy, exhibits new forms of power through state racism. Under the classical Westphalia definition, the nation-state concept has one language and one culture. However, the Chinese constitution attempts to portray a non-Westphalian and alternative model, one that promotes ethnic languages by officially recognizing 56 ethnic minorities. It is an attempt to showcase an inclusive China that can be a nation-state with multiple cultures. However, the reality is that China has been unable to achieve that idea because the history of modern China is a history of occupation, whether in Tibet, East Turkistan, or Mongolia. At present, under Xi Jinping, his approach towards minority language and education has become much more aggressive, including his language policy, implementation of boarding schools, and hardening of ethnic unity. This shift itself is an indication of Xi Jinping’s acknowledgment of the failure to achieve the goal of an inclusive China and live up to its constitution. The new language policy under Xi Jinping thus acknowledges that their idealism has failed because the reality is incompatible with the underlying idea of occupation. Therefore, at present under Xi Jinping, there is a greater push for China to act like a Westphalian state, that is one state, one language, where everything has to be defined and seen under Chinese ‘socialist characteristics’ whether it is education, language, or religion. Under Xi’s ongoing aggressive policies against protecting domestic culture and promoting Han culture, there is a debate about removing minzu. In today’s China, the Chinese nation is called “zhonghua minzu”, and the 56 ethnic groups within China are called 56 “minzu”.

Language Demography

China is the second largest population globally, with 1.4 billion people living in China today. It is a multi-ethnic country with officially recognized 55 minority groups making up 110 million people in China. Around 90 percent of the population is Han, a dominant group that speaks Chinese or Mandarin, while the minority groups have their own languages that are protected under the Chinese constitution. Tibetans and Uyghurs constitute a majority among the minority languages with the two largest territories in Western China. Recent research identified that 128 languages are spoken in China in addition to Mandarin. The nationwide promotion of Mandarin Chinese as a national language in 1956, the provision of Mandarin Chinese starting from Grade 3 in minority regions, and the popularity of Mandarin Chinese because of globalization and China’s trade relations with the world have created unfavorable positions for minority languages in China.

| Region | |||

| Population | Dialect | ||

| U-Tsang | TAR | 2,096,346 | U-Tsang |

| Kham | Yunnan | 126,618 (2010 census) | Kham |

| Sichuan | 1,087,510 | Garze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture (population 880,000), 78.37% of residents speak Kham dialect; and in Muli Tibetan Autonomous County (population 40,312) about 32.39% of Tibetan residents speak Kham Dialect

Tibetan population in Aba Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture (455,238, 53), and 72% of whom speak Amdo dialect |

|

| Amdo | Qinghai | 911,860 | From total population of Tibetans in Qinghai (288,829), 97.25% speak Kham Dialect (2005 Yushu Statistical Yearbook) |

| Gansu | 366,718 | Tibetan population in Tianzhou (Bare) (66,125), and 29.87% of them speak Amdo dialect (2000 census); Tibetans in Sunan county (about 8,393) speak both Amdo and U-Tsang Dialect |

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s43545-021-00092-y/tables/1

History

Tibetan language dates back to the 7th century and belongs to the Tibeto-Burman branch of the Sino-Tibetan macrofamily, which is completely different from the Chinese language in its grammar, vocabulary, and script. For more than a thousand years, the Tibetan language has been used to teach, learn, and transmit knowledge. Tibetan traditional learning, knowledge, and practices are quite unique on their own.

After the invasion, the turbulence and changes that took place in Tibet had the most crushing and costly impact on Tibet’s traditional educational system. The newly founded Communist China applied its own educational policy in Tibet that was largely based on the Soviet model.

China was the new colonial power in Asia, subjugating Tibet and depriving Tibetans of their rights, especially their right to speak and learn their own language. With China officially incorporating Tibet under its minority groups as against the Han majority which makes up 90 percent of the population, Tibet was marginalized in all senses and was deprived of any authority to make its own language policy. In fact, authors like Luo Jia and Pai Qie noted that the Chinese central government implements policies without any adaptation in light of regional and local situations.

Under the new colonial rule, not only was Tibetan language and culture viewed as “backward” as opposed to Chinese culture as the “civilized” one, but Chinese officials often undermined minority rights to language and culture as stipulated in the 1982 Constitution of the PRC and PRC Regional Autonomy Law for Minority Nationalities in 1984, state Yuxiang Wang and JoAnn Phillion. The regional autonomy law states that minority nationalities have the right to “conduct affairs in their own languages and independently develop education for nationalities.” In the 1995 Education Law, it states that “schools and other institutions for minority nationalities can use the common language of the ethnic group as the language of instruction.” Gerald Roche, whose book “The Politics of Language Oppression in Tibet” will be out soon, notes that, even though the state may recognize or say they support the use of an ethnic minority group’s language, there is a lack of institutional support compared to Putonghua (modern Chinese), inevitably causing minority languages like Tibetan to be sidelined.

Language under Constitution

As stated in Article IV in the 2018 edition of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China, the federal government recognizes all ethnic minority groups as equal, and the state has a responsibility to protect the “lawful rights and interests of all ethnic minorities.” Though the constitution stipulates that minority groups have the freedom to use their own minority languages, implementing official federal minority language policies is contrary to this constitutional provision.

Furthermore, the PRC constitution ensures the protection of minority rights to language and culture but with an emphasis on upholding the unity of the country. Since the law prioritizes the country’s unity over minority rights, the constitution practically empowers the state to rule over minority rights if they are deemed to violate or harm the country’s unity. There is no point in guaranteeing minority rights in the PRC constitution when anything that does not fit into China’s version of unity, which equals homogenous Han culture and regards other minority cultures and languages as threats to national unity, and use of Tibetan language, for instance, is deemed an act of separatism. Which is why scholars noted that teaching in Tibetan was abandoned as part of the post-1989 crackdown on separatism that resulted in the current situation of subjects being taught in Chinese only.

There is also a gradual shift in the emphasis of the use of language from minority language to Mandarin Chinese on the policy level. Although the emphasis has always been on national unity and national security over protection of individual rights, the legal aspect of language rights and freedom to practice one’s language gradually took on different meaning and interpretation, leading to implementation of various laws that render minority languages, in this case the Tibetan language, in a state of redundancy. Following the implementation of the Law on Education in 1995, minority languages shifted from being the principal language to being an extracurricular language, with Mandarin Chinese becoming the language of instruction. The adoption of the Law on the National Standard and Spoken Language in 2000 further made the use of Mandarin Chinese prevalent.

The national promotion of Mandarin Chinese led to even changing the school curriculum to be taught in Chinese language with a heavy dose of Han Chinese cultural norms and party ideology. Mandarin Chinese, also known as Putonghua, is gradually taking over as the main language of instruction, even in those regions where officially categorized “minority languages” have been protected and institutionalized in primary and secondary schools. Both legally and practically, promotion and inducement of Mandarin Chinese as the medium of instruction reduces access to one’s own language, education, history, and culture, and can cause the loss of heritage and identity. The marginalization of minority languages is seen as potentially eroding ethnic minority identities and leaving affected social actors with a sense of frustration, displacement, and disempowerment.

The reasons and rationale behind the deprived state of minority languages under China’s rule are, firstly, due to the overarching idea of national unity above all else; the increasing idea of securitizing Tibet and Tibetans, thereby looking at Tibet primarily through national security, leaving Tibet and its culture to be classified either as a threat or a non-threat (but mostly seen as a threat); but in China’s understanding, it has now been widely established that anything that is not Han culture is relegated as a threat to national unity. There is also distrust between Chinese officials and Tibetans, and a strong prejudice against minority culture and language. Therefore, suppression of minority languages in China by making Mandarin Chinese the official language and medium of instruction in schools became part of China’s policy of assimilation.

Xi Jinping’s Latest Campaign in Tibet

In June 2024, Xi Jinping’s visit to a middle school for Golok Tibetans and a Tibetan Buddhist Temple in Qinghai made an effort to deepen education to forge “a strong sense of community for the Chinese nation.” Xi’s visit highlighted his priority in the region by meeting the provincial representatives to stress the importance of cultivating national unity, Sinicization of religion, and strengthening the management of religious affairs. Xi Jinping has worked to implement two primary goals: securitize Tibet and Sinify the Tibetan people in the Chinese nation-state as part of his long-term assimilationist drive. While addressing a Politburo study session in December 2024, Xi Jinping called for Mandarin to be spoken more broadly in the border region along with national security and social stability to be upheld. Xi highlighted during the party’s top policymaking body that ethnic groups in border regions should “continuously enhance their recognition of the Chinese nation, Chinese culture and the Communist Party.” He also said the use of the common Chinese language, Mandarin, and nationally unified textbooks should be promoted.

In 2021, when Xi Jinping visited Lhasa, he called on local officials to strengthen national unity and patriotic education to counter separatism. His frequent tours around Tibetan regions were seen as refocusing on his key policy priorities, particularly on maintaining stability and development of the region. A scholar notes that Xi’s visit pronounced key elements from his policies on Tibet: that Tibetan Buddhism’s “adaptation to socialism and Chinese conditions” and the strengthening of ethnic unity by stepping up political and ideological education.

Cases to show intensification of language suppression under Xi Jinping

Language advocates in Tibet met with torture and detention

Gonpo Namgyal, leader of Ponkor Village in Qinghai province’s Dharlag county, or Dari in Chinese, who was arrested last year for advocating for preservation of Tibetan language, died three days after his release with electrical burn and torture marks found on his body. A village chief who was detained in May for championing Tibetan language preservation was arrested along with 20 other Tibetans in May for engaging in activities to promote the preservation of Tibetan language and culture. In 2018, a Chinese court sentenced a Tibetan man, Tashi Wangchuk, to five years in prison because he advocated for Tibetans’ right to their own language, a right protected by Chinese law. In 2019, another Tibetan man, Tsering Dorje, was detained for a month in a so-called reeducation facility for discussing the importance of the Tibetan language with his brother over the phone—the Chinese authorities framed this as a political crime. Gong Lajia (also known as Tashi Nyima), an Internet celebrity from Dêgê County, Garzê Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, a part of historical Tibet now in the Sichuan province, gained fame for promoting the Tibetan language on Chinese social platforms. On August 28, as he announced himself in a video, he was arrested by Dêgê County police during a live broadcast.

New Restrictions imposed

In January 2025, during the two-month-long winter break, Tibetan students in the capital Lhasa and across Tibet are prohibited from receiving tutorials outside of school-planned assignments or taking private lessons in the Tibetan language, they said. Instead, authorities have instructed students to focus on improving their Mandarin-language skills by taking lessons to further enhance their proficiency.

Crackdown on online language platforms

The Chinese authorities have intensified efforts to curtail the use of Tibetan language across various mediums, including blogs, schools, websites, and social media platforms like TikTok (Douyin). Recently, the Chinese authorities have blocked access to Luktsang Palyon, a prominent Tibetan-language weblog that was a great source for educational content, articles, stories, translations, and audio resources for Tibetans since 2013. Today, even using online platforms to express in Tibetan has been banished. The Chinese version of TikTok, which is popularly called Douyin, has removed the Tibetan language. Many Tibetan netizens came forward condemning the Chinese government’s decision to ban the Tibetan language from online platforms. Article 4 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China clearly states that all nationalities of the PRC are equal and have the freedom to use and develop their own spoken and written languages.

Closure of Tibetan schools

Since 2021, authorities have forcibly closed numerous private schools and primary schools in monasteries that specialized in Tibetan language education. On 12 July 2024, the Chinese government forcibly ordered the closure of the award-winning Jigme Gyaltsen Nationalities Vocational High School in Golog, Amdo. Previously in June, the Taktsang Lhamo Kirti Monastery school, which had about 500 students, faced increasingly strict restrictions until it was finally closed. On 31 October 2021, not only was the Drakgo Monastery’s Gedhen Nangten School closed, but the classrooms, dormitories, and other facilities were also demolished. In July 2021, without giving any official reason, the Chinese authorities in Golog, eastern Tibet, ordered the shut down of a private Tibetan school, Sengdruk Taktse middle school, in Darlak County. On 1st August 2021, Rinchen Kyi, one of the longest serving teachers at Sengdruk Taktse Middle school, was arrested in Golog, eastern Tibet, on the charge of inciting separatism under Chinese law. The Chinese authorities in Golog forcefully shut down Sengdruk Taktse Middle School, a renowned school, in early July 2021, and Loten, a college graduate student, was arrested after he spoke in an online messaging group on WeChat expressing disagreement with the policy of Sinicization of the education system in Golog. He has since been kept in a detention center in Xiling City. The crackdown intensified in 2022, when three additional schools were forced to cease operations across Karze Prefecture: The Phende Care School in Dzakhog County, the Private Primary School in Chaktsang Center, and the Gyalten Foundation School in the Trehor Dargye Rongpatsa area. According to information released by the Ngaba Prefecture’s Nationality and Religious Affairs Committee in July 2024, before the closure of the Taktsang Lhamo Kirti Monastery school, 69 primary schools throughout Ngaba Prefecture had been completely closed, 8 schools were merged with other schools, and 33 primary schools had their educational systems changed in accordance with the 14th Five-Year Plan of Ngaba Prefecture.

New Education Policy

Representation of the Tibetan language in Tibet by prioritizing Chinese, making it look bigger in public institutions, road signs, and in other areas naturally creates an impression that the Chinese language is preferred over Tibetan. The Chinese government is forcing the erosion of the Tibetan language as a medium of instruction in schools in Tibet, contrary to its own laws and international obligations. Kindergarten and elementary schools in Tibet are teaching students Chinese rather than Tibetan, risking the children’s development and the survival of Tibetan culture. Nearly all middle schools and high schools in the Tibet Autonomous Region have been teaching students in Chinese since shortly after China annexed Tibet, a historically independent country. The new education policies introduced by the Chinese government are now also leading kindergartens and elementary schools in the TAR to teach students in Chinese instead of Tibetan. The new policies seem aimed at indoctrinating children with Chinese propaganda from a young age and cutting them off from Tibetan culture and history.

Outline

- 1949: The establishment of the People’s Republic of China and Tibet came under complete occupation

- 1952: The first state school was established in Lhasa where the teaching was in Tibetan but the content was heavily influenced by Chinese communist propaganda.

- 1956-1958: The bilingual primary schools were established

- 1976: With the death of Mao and the rise of Deng Xiaoping, specific educational programs for minorities were developed throughout Tibet.

- 1982: An education policy was put in place in the TAR that stated that Tibetan was to be the primary language of instruction. This did not change in middle and high schools, where Chinese remained the language of instruction, but almost all Tibetan primary schools began to offer Tibetan-medium instruction for all classes except those teaching Chinese language (Putonghua) itself, which was taught as a single subject from the third or fourth grade onwards.

- 2001: To improve students’ abilities in the Chinese language, urban schools in the TAR began teaching Chinese as a language from the first grade upwards instead of from the third grade.

- 2002: In July 2002, China’s State Council ordered officials to “vigorously promote ‘bilingual teaching’ in minority nationality primary and secondary schools,” but noted that schools should “correctly handle the relationship between usage of the minority nationality language as the teaching medium” and Chinese as teaching medium.

- 2005: China’s State Council issued suggestions for “minority nationality areas to gradually promote the ‘bilingual teaching’ of minority nationality languages and Chinese-language teaching.”

- 2008: A law on compulsory education in the TAR required that all schools introduce “bilingual education.” It specified only that this meant these schools had to “popularize” Chinese-language “education.” It did not state whether this referred only to increasing the study of Chinese language, or whether it meant introducing Chinese-medium instruction.

- 2010: China’s Ten-year Education Plan in 2010 announced that “no effort should be spared to advance bilingual teaching, open Chinese language classes in every school, and popularize the national common language and writing system … to ensure that minority students [have] basic grasp and use of the national common language [Chinese].” It said “minority people’s right to be educated in native languages shall be respected and ensured” and made no mention of using Chinese as the medium of instruction.

- September 2014: At the Central Authorities’ National Conference on Ethnic Work, President Xi Jinping indirectly confirmed the moves towards Chinese-medium education in minority schools by announcing that overall ethnic policy would henceforth aim at promoting “ethnic mingling” and “cultural identification” with “Chinese culture.”

- October 2014: A major party document from the Central Party Committee instructed all schools in China, particularly those with minority nationality students, not just to “fully popularize the national language,” but also to “resolutely push forward education in the national language and script” as well as to “fully hold classes in the national language,” seemingly indicating a requirement to switch to Chinese-medium education at all levels.

- 2015: China’s State Council issued its “Decision on Ethnic Education,” which required “bilingual education” to be “comprehensively popularized” in all schools in minority areas where use of Chinese is “weak,” but did not specify what this meant in practice.

- 2015: The TAR announced that it had “basically completed the bulk of its mission of building a bilingual education system” and that 97 percent of all Tibetan students in the TAR were receiving “bilingual education.”

- 2017: The TAR announced that “bilingual education” in primary and middle schools had achieved “100 percent coverage,” but did not specify what this meant in practice.

*collected from Human Rights Watch report on China’s “Bilingual Education” Policy in Tibet published in 2020

——

*Dr. Tenzin Lhadon is a research fellow at the Tibet Policy Institute. Views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the Tibet Policy Institute.