The octogenarian emperor of the Qing dynasty, Qianlong in September 1793, was to receive a delegation from an island nation, whose mercantile organisation, East India Company was sweeping across India, drawing spices and raw materials to serve its factories. When the British trade mission led by George Macartney arrived at the court of the Qing dynasty assisted by a 13-year old interpreter, exchange of elaborate gifts ensued. A particular model of HMS Royal Sovereign caught the emperor’s fancy in the light of the empire’s shoddy defence of its shores.

The concerns over burgeoning British maritime power were not misplaced as half a century later, a war that began in 1839, China’s market would be forced open as attempts to thwart hugely profitable opium trade hauled from the plains of India failed. This marked what even to this day to many Chinese, the beginning of the ‘century of humiliation.’

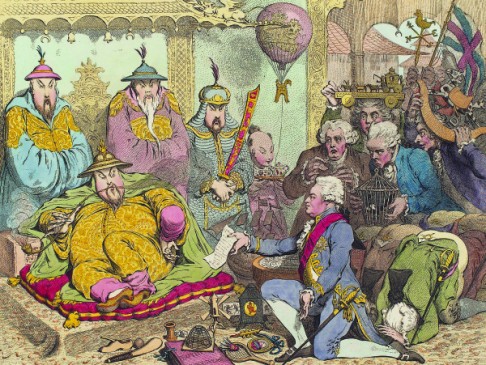

A satirised impression by an artist when the Macartney Embassy was received at the Qing court

Announcing its supposed arrival at the world stage, President of the People’s Republic of China, Xi Xinping paid a visit in January this year to a picturesque Swiss ski resort in Davos, where global elites gathered to mull over the direction the world is heading. He gave a speech in defence of globalisation, interspersed with literary quotes from Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. In a beleaguered world when the bedrocks of globalization were questioned across the political spectrum, it is China’s turn — as an opinion of Forbes describes — to sound “reasonable, conciliatory, patient, ready to assume the mantle of leadership that so many are so eager to thrust upon it.”

The proponents of a neatly drawn idea of China’s benign civilizational state are either academics enamoured with China’s rise or Chinese scholars convinced of their state’s might. This concept stems from flawed assumptions and glaring historical omissions. Some of its great empires that ruled China were outsiders and the last in the long line were the Manchus. In its long glorious history, the Chinese empire had often been laid siege to, overthrown and ruled by the non-Han minority of modern China. In the altars of Communist China’s statecraft, Mao serves as a patron and a leading figure. To draw legitimacy of China as a civilizational state would be to sow contradictions in terms of its provenance.

Modern China state and its policies are a progeny of uncomfortable union of Marx and Adam Smith’s ideas. Its Marxist-Leninist policy concerning the management of its diverse ethnic minorities and economic policies of capitalistic fervour with state intervention overrules the invisible hand of a market economy.

Sikyong Lobsang Sangay, the political leader of the Central Tibetan Administration, on the eve of his visit to the UK penned a plea in the Guardian, beseeching British government not to forget Tibet in dealing with China. This was met with a quick rebuttal by the spokesperson of the Chinese embassy in the UK, claiming ‘Chinese policy is modernising Tibet.’

Maintaining the colonial project comes at a cost coughed up from the state’s coffers in Beijing. An often cited impressive piece of statistic that Tibet’s GDP growing at 12.4% over the past two decades belies the reality of Tibet’s domestic economy. According the most reliable data available to us, Tibet’s local economy is dwarfed by subsidies which at times reaches 112% of its economic output. This led to a long-time observer and authority on Tibet’s economy, Andrew Fischer to remark that state of Tibet’s economy and its dependency on subsidy is “more than one would see in a highly aid-dependent African country.”

The best way to make sense of modern China is by viewing China as a colonial state. China, after successfully co-opting the elites of its colonised territories and bureaucrats competent in Chinese — not unlike the Macaulian babus that pushed pens and kept books in Writer’s building in Calcutta in service of the Raj — elites in these colonised territories remained the largest beneficiaries. The vast majority of the population watched helplessly as their economy and traditions were dismantled, a veneer of modernisation greets tourists’ eyes.

The tentacles of Chinese political ambitions are now spreading far beyond its colonial territory. The vehemence of China’s adventures in the South-China Sea where military bases are set up on reclaimed islands and curious incidents where journalists and influential businessmen based in Hong Kong vaporise and mysteriously reappear in mainland China, confessing untold crimes.

The violence and brutality of China’s colonisation of Tibet is real to a vast majority of Tibetans living in Tibet. In a recent report published by the Freedom House, for the second year in a row, Tibet is found to be the second least free place in the world, with only war-torn Syria ranking lower. Since 2009 there have been 145 confirmed self-immolations within Tibet. Tibetan institutions for learning are under severe threat as evidenced when one of Tibet’s largest Buddhist learning centre was dismantled and monks and nuns were forcefully expelled in convoy of buses.

On 27 May, 2015, Sangye Tso, a mother of two set herself on fire outside a government office and she eventually succumbed to it. In a handwritten note she left she is reported to have written: “Long live His Holiness the Dalai Lama, where is the Panchen Lama, and freedom for Tibetans.”

____________

*Tenzin Desal is a research fellow at the Tibet Policy Institute. Views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the Tibet Policy Institute.