Introduction

With the acceleration of urbanization and the Chinese government policy in reducing the cost of mineral transportation and other factors, the construction of the Tso-ngon -Lhasa Railway in the Tibet plateau has started at the beginning of 2007. This railroad provides a major access route into Tibet from Siling to Lhasa which extends to 1118 km. The construction began in 2001 and was completed in 2006 despite the challenges faced by the engineers in building the railroad across an unstable landscape. The Tso-ngon-Lhasa Railway is said to be the highest elevated and the longest railway across a permafrost region in the world.

In the early 1950s, due to unstable roads and poor transportation, traveling within and out of Tibet would take nearly from six months to a year. According to Evelyne Yohe and Laurie J. Schmidt, sometimes China was forced to use camels to transport cargo to Tibet. It is said that 12 camels on average, died for every kilometer the caravan traveled across the Tibetan Plateau and over high mountain passes.

According to Tingjun Zhang, a scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado, “The Tso-ngon Lhasa railroad is the most ambitious construction project in a permafrost region since the Trans-Alaska Pipeline.” He studies the effects of climate change on permafrost areas all around the world.

However, building a railroad across the highest plateau in the world is hugely risky. Due to the thin air on the high plateau, non-acclimatized workers risk of nosebleeds, blackouts, and even death. Due to this, they need to carry oxygen bags, undergo daily medical monitoring, and work no more than six hours a day. To avoid prolonged exposure to the extreme climate conditions, workers rotate off the plateau every few weeks. In addition to the risks associated with construction at high altitudes, the biggest challenge of building a railroad faced by the engineers across an unstable landscape was the permafrost. The total length of the railway in permafrost regions is approximately 550km and approximately 82km passes through discontinuous permafrost. Permafrost along the railroad lies in the eastern regions of the plateau.

Permafrost is defined as the ground with a mixture of soil, gravel, and sediment bound together by ice that remains at or below 0°C for at least two or more consecutive years. As one of the main components of the cryosphere, permafrost secures highly compressed carbon and methane gases created from decomposed organic remains which are the leftover materials from dead plants that couldn’t be decomposed due to the extreme cold weather. Permafrost in the Tibet plateau covers 1.06 x106 km2 or approximately 40% of the area of the plateau. This permafrost is highly sensitive to climate change and surface disturbances, especially to air temperature changes and is also considered the indicator region for climate and environmental changes. Outside of the Arctic and Boreal biomes, the Tibet plateau contains the largest permafrost region and is the source of the most major Asian rivers such as the Yangtze, Yellow, Indus, and Mekong. The Tibet plateau serves as the Water Tower for nearly 1.4 billion people (Yao et al., 2019). The Tibet plateau also plays a vital role in the stability of Asia’s climate system, water supply, biodiversity, and regional carbon balance making it crucial for the global biosphere integrity and sustainability of the surrounding areas.

Persistently warming climate due to accelerated temperature and anthropogenic interference increase has contributed to widely degraded permafrost across the Tibet plateau. Permafrost thawing is more dominant under engineering conditions than in natural conditions. The permafrost beneath the track experiences the combined effect of climate change and construction thermal disturbance. Slight changes in permafrost may cause embankment damage. Scientists and engineers charged with monitoring permafrost along the Tso-ngon-Lhasa railroad’s route are primarily concerned with the layer that lies directly above the permafrost, known as the active layer, which freezes and thaws seasonally. The active layer generally melts from April to September and freezes from October to March. Changes in the active layer may affect carbon pools and carbon flux. Soil carbon which is stored in large amounts in the permafrost represents an important potential carbon source under the influence of climate warming and can trigger a strong permafrost carbon-climate feedback. Due to climate warming, longer periods of seasonal thaw can cause the active layer to slump, causing the soil to shrink and anything constructed on top of it to shift and are vulnerable to collapse. As the ground thaws and freezes, it contracts and expands, putting stress on the foundations and twisting rail tracks. Due to the railway operation on the permafrost regions, the hydrothermal balance of the active layer has also been disturbed leading to the permafrost subsidence.

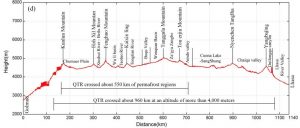

Fig 1- Vertical sectional profile graph of the railroad from Gormo to Lhasa (Jing Wang et al, 2019)

The railroad crosses many high-altitude mountains, such as Hoh Xil Mountain (ཨ་ཆེན་གངས་རྒྱབ)།, Kaixin Mountain, Fenghuo Mountain, Tanggula Mountain(གདང་ལ་རི་བོ།), Tou Erjiu Mountain, and Nyenchen Tanglha(གཉན་ཆེན་ཐང་ལྷ།) respectively. Other sections of the railroad belong to high plain landforms with flat terrain. The rivers across the railroad include Kunlun River, Chumaer river, Beiluhe, Tuotuohe(ཐོག་ཐོག་ཆུ་བོའི་འབབ་ཚུགས་), Yangtze River, Buqu River, Za gya Zangpo river(རྩ་སྐྱ་གཙང་པོ།), Tongtian river, Nujiang River(རྒྱལ་མོ་རྔུལ་ཆུ), and Yarlung Zangpo River. Along the railroad, the area at an altitude of 4000m high is 960km long and the temperature is -10°C in many places year-round. The frozen soil layer thickness is greater than 60m and the average active layer thickness ranges from 0.8m to 4m with a mean of about 2cm.

The long-term observation of permafrost along the railroad has indicated that permafrost subsidence and thermal melt collapse are the common hazards affecting the stability of the railway embankment. Due to the construction of the railroad, the original thermal balance of the active layer has been destroyed leading to high subsidence in the permafrost regions. The sections with high subsidence values include Gormo-Xidatan, Budongquan(ནག་རི་ཆུ་ནག་ཁ)- Hoh Xili, Wudaoliang(སྨིག་པ་ལ་སྒང) —Wuli, Tuotuohe—Yanshiping(བྲག་སྨུག), Tanggula Mountain(གདང་ལ་རི་བོ) pass—Amdo, Naqu(ནག་ཆུ)—Damxung(འདམ་གཞུང), and Yangbajing(ཡངས་པ་ཅན)—Lhasa. Several thermokarst lakes have also developed near the railroad, such as Zonag Lake(གྲོ་ནེ་མཚོ་) Kusai Lake(་ཨ་ཆེན་གངས་) and Salt Lake(ཚར་ཧན་ཚྭ་མཚོ)་The thermokarst lakes and thaw slumping has also been observed more frequently in the permafrost areas such as the Beiluhe region and Fenghuo Mountain. Some thaw slumps have also been observed in the Tuotuohe region through the time series of SAR maps.

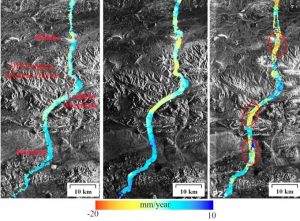

Fig2- Estimated ground deformation rate in the three regions a) 1997-1999 b) 2004-2010 c) 2015-2018 (Zhengjia Zhang et al, 2019)

The permafrost of the Xidatan area which is located at the glacial alluvial plain of Kunlun Mountain consists of mostly iron-shaped frozen soil. It is also observed that there are some glaciers and seasonal run-offs from the Kunlun Mountains. Due to the recent temperature rise and human activities, some glaciers have melted, and soil moisture also increased which caused subsidence in that area.

Yuzhu peak which is the highest peak in the eastern part of the Kunlun Mountains is covered by snow and ice and there are several seasonal run-offs from Yuzhu peak caused by melting glacier water. Melting of glaciers has been higher than the accumulation rate.

Before the opening of the railway in 2006, the ground deformation along the railroad was very minimal. However, the overall mean deformation rate has changed significantly after the opening of the railroad. The overall mean deformation rate at the beginning and the end of railroad was within 10mm/year. Based on the 3years (2015-2018) of InSAR observations (see figure 2), three regions with serious ground deformation have been detected. They are Beiluhe, south of Fenghuo Mountain and Tuotuohe. The modeled MAGT (Mean Annual Ground Temperature) of these three sites was also conducted. MAGT factor is also an important factor that extremely impacts the extent of embankment deformation in the permafrost regions. The MAGT was the lowest for the Fenghuo Mountain areas with a temperature of less than -2°C and the highest is for the river valley areas of Tuotuohe with a temperature above 0°C. For the Beiluhe basin areas, the MAGT ranged from -2°C to 0°C. High MAGTs would contribute to the increase in permafrost thawing and then lead to ground deformation around the regions of the railroad.

Socio-Economic Impacts of the Railways

The construction of the railroad has socio-economic impacts as well. Lhasa and its areas have become the most visited areas in Tibet since the operation of the railroad. However, the economic development of the country has generated a strong demand for livestock raising. The main industry of Amdo, Nagqu, and Damxung is animal husbandry. The traditional nomadic lifestyle in this area is disappearing quickly. Instead, the modern urban lifestyle is now much more common among Tibetans in Tibet. The alpine ecosystem has therefore evolved because of frequent anthropogenic activities which have resulted in the over-exploitation of grassland resources. This condition has led to more threats to livestock farming and pasture management and affecting alpine grassland ecosystems. At present, the main problem associated with the grassland restoration project is that the funds for the project in Tibet are less than 5000 yuan per capita per year which is lower than the annual grazing income of herdsmen and thus affects the enthusiasm of herdsmen to participate in the project. Moreover, 6.97 million hectares of grassland have been fenced since 2008. During this process, pastures have been fenced and grazing areas have been reduced.

Effects of the Tso-ngon – Lhasa Railway on the wildlife: A case study of Przewalski’s Gazelle

The Tibet plateau has sheltered some of the most unique animal species including many endangered species. Endemic to the plateau, the Przewalski’s gazelle is arguably one of the most endangered large mammals in the world. Historically, P.przewalskii was widespread across the semi-arid grassland steppe in the northeastern part of the plateau but has suffered a severe population decline due to anthropogenic disturbances. Overall human settlements and infrastructure development have restricted the movement of most populations and posed severe threats to the sustainable survival of Przewalski’s gazelle. Haerghai County which is located on the east side of Qinghai Lake is home to the largest number of Przewalski’s gazelle accounting for 40% of the species’ total population. The construction of the railway has made it impassable for the animals except by the bridges and culverts. The influence of the railway on the surrounding environment and wildlife has been a major concern since its construction. The railroad which runs across the Haerghai County divides the gazelles’ region into two sub-regions, namely Haerghai North (N) and Haerghai South(S) regions. To the northeast of the railway, the Talexuango population is separated from the Haerghai North by the highway G315 which was constructed in 1954. This highway unlike the railway is not fenced or enclosed hence, the gazelles from Haerghai North have been observed moving across to Talexuango in the north. There are eight culverts underneath the railway constructed to allow for pedestrian or water flow along the 10km Haerghai North-South boundary, hoping that it might mitigate the negative effects of the railway on wildlife. However, there were no signs of the gazelles crossing these passages. This has been found from a survey from 2007- 2009 despite having the shortest physical distance between them. Hence, the railway remains the most likely unbridgeable barrier for the gazelles from Haerghai north and Haerghai south and considers it as two isolated populations. These isolated populations became more vulnerable to environmental stochasticity. The two sub-regions segregated by the railway, P.gazelle from Haerghai North and Haerghai South had a very low migration rate (0.0683 and 0.0242). The presence of a railway has effectively blocked the gene flow between the two sub-regions, thus resulting in a detectable level of consequences of genetic differentiation.

Engineering Techniques

To defend against the structural damage of permafrost thawing, engineers have developed various engineering control methods for maintaining permafrost stability. Such as the crushed rock embankment in warm and high ice content permafrost regions. After this measure was applied, permafrost temperatures decreased, and the permafrost table was raised. The permafrost table is said to be the upper boundary of permafrost. The Cold and Arid Regions Environmental and Engineering Institute in Lanzhou, China, tested a crushed rock layer in a section of railroad embankment that overlaid permafrost. After one year, the section was significantly colder than before the installation of the rock layer. However, some parts of the plateau are covered with sand dunes. Unlike the mud, its grains don’t stick together and are blown towards the railway embankment which is half a kilometer away. Hence, the sand blown permeates and fills up the gap in the crushed rock embankment. As it fills up with sand, it loses its ability to cool the ground below and leads to permafrost thawing. However, this technique was not effective for the general embankment for some sections of the Tso-ngon-Lhasa Railway. Although the maintenance costs of the crushed rocks embankment are extremely low, installation of crushed rock is labor-intensive. However, the crushed rock did not produce enough cooling in the warmer permafrost ground.

Some experiments were conducted in the early 1970s, where large concrete ventilation tubes were placed beneath the test railway embankments to allow airflow. Hence, the embankment stayed frozen. This technique was discovered by people who have been living on this land for thousands of years. To survive the constant degradation of permafrost, houses built on the plateau have employed simple yet ingenious technology for its foundations. The large ventilation tubes placed beneath the railway embankments have air gaps that insulate the ground from heat generated inside the building. If the pipes are cleared, the permafrost does not melt. However, it was prove to be ineffective in more fragile permafrost areas.

Another solution was the thermosyphons also known as heat pipes. They are the metal tubes that look like stovepipes jutting out of the ground. They are about 10 meters long and up to 5 meters buried into the ground with 20cms in diameter with about 9 liters of ammonia in the bottom layer. Thermosyphons do not need electricity to apply to work. The ammonia inside it boils at low temperature drawing heat from the surrounding earth; hence 34kms of the railroad track were cooled this way. However, even thermosyphons were not sufficient in the most fragile areas of the warmer permafrost. Thermosyphons are costly to install and maintain and they must be placed along the entire length of a railroad.

For a better and more effective solution, the engineers decided to avoid the permafrost areas and built bridges over the top of them. There are around 675 bridges on the railway crossing the railroad. Yet the biggest concern was to insert the concrete piers.

Despite the huge investments in the innovative technologies used while building the railroad, however, just after a month of the operation of the railroad in 2006, the state media made a rare admission that fractures started to appear in some railroad bridges because of permafrost movements under the rail bed. Therefore, it is still uncertain about the railroad’s sustainability.

Conclusion

- Even though the railroad has strengthened the economic linkages between cities both within and outside the Third Pole, however the impact of the railway on permafrost thawing could release huge amount of trapped carbon and methane gases which ultimately leads to the global warming.

- Conservation measures should be taken immediately to prevent the further loss of genetic diversity for the survival of Przewalski’s gazelle such as building wildlife friendly corridors over the railroad and the reduction of human disturbances are recommended.

- Protection of wildlife is not only important for the preservation of nature or nomadic heritage but also for the ecological heritage of all Asia.

- The permafrost-protecting techniques on the railway are to date reported as effective ways to stabilize the permafrost. However, sustainability has a temporary meaning, suggesting that what we currently consider to be sustainable may become unsustainable in future.

Works referenced for this paper

- Environment and Development Desk, Impacts of Climate Change on the Tibetan Plateau: A synthesis of Recent Science and Tibetan Research (Dharamshala; DIIR, 2009).

- Zhao L et al., “Changing climate and the permafrost environment on the Qinghai-Tibet (Xizang) plateau,” Permafrost and Periglac Process. 2020; 1-10.

- Guo D et al., “A projection of permafrost degradation on the Tibetan plateau during the 21st century,” Journal of Geophysical Research. 2012; 1-15.

- Wang G et al., “Freeze-Thaw Deformation Cycles and Temporal-Spatial Distribution of Permafrost along the Qinghai-Tibet Railway using Multitrack InSAR Processing,” Remote sensing, 2021;1-30.

- Qin Y et al., “The Qinghai- Tibet Railway: A landmark project and its subsequent environmental challenges,” Environment Development and Sustainability, 2010; 860-870.

- Gao H et al., “Permafrost Hydrology of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau: A Review of Processes and Modelling,” Front Earth Sci., 2021.

- Yu H et al., “Effects of the Qinghai-Tibet railway on the Landscape Genetics of the Endangered Przewalski’s Gazelle (Procarpa przewalskii)” Scientific Reports, Article number 17983. 2017.

- Troy Sternberg and Kemel Toktomushev ,eds, The Impact of Mining Lifecycles in Mongolia and Kyrgyztan (London: Routledge, 2022), e-book.

- Mu C et al., “The status and stability of permafrost carbon on the Tibetan Plateau” Earth Science Reviews, 2020; 103433.

- Zhang Z et al., “Permafrost Deformation Monitoring Along the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Engineering Corridor Using InSAR Observations with Multi-Sensor SAR Datasets from 1997- 2018”, 2019.

- He G et al., “Environmental Impact Assessment and Environment Audit in Large Scale Public Infrastructure Construction: The case of the Qinghai-Tibet Railway”, Environmental Management., 2009; 580-587.

* Ms. Tenzin Youdon was a research intern at the Tibet Policy Institute. She holds a Masters in Environmental Science from Banaras Hindu University (BHU). Views expressed here do not necessarily reflects those of the Tibet Policy Institute.